Kiosk Software Evolution

Without those who took the first steps in developing software for kiosks, the industry wouldn’t be enjoying its current dominance in the marketplace.

By Richard Slawsky contributor

There’s a saying in the business world along the lines of “The pioneers get the arrows.” Nowhere is that more applicable than in the world of kiosk software.

But before we get head down that road let’s remind ourselves of some of the current dedicated software companies.

- KioWare – kiosk lockdown & secure browser with monitoring

- Nanonation – custom kiosk software & digital signage

- PROVISIO – kiosk software secure browser w/ remote monitoring

- Acquire Digital – advanced digital sign technology software

- Self-Service Networks – Gift Card software for Malls and more.

- NEXTEP SYSTEMS – self-order software POS for QSRs and more

- DynaTouch – kiosk software, lockdown & turnkey wayfinding

- ——— Companies with Both Hardware and Software ———

- KIOSK Information Systems – software and hardware

With kiosks now becoming an integral part of society, and poised to take an even more dominant position in the marketplace this year, it might be interesting to take a few minutes to pay homage to the pioneers of kiosk software.

And while it’s impossible to name every player who made their mark in the early days of the kiosk, there are a few whose impact still resonates throughout the industry.

The beginnings

Of course, one of the key drivers behind the development of kiosk software was the explosion of computer industry, beginning in the late 1970s. While computers had been around for decades, products such as the MITS Altair 8800, the IMSAI 8080 and the Apple 1 not only made computers more affordable than their predecessors, they gave birth to the concept of desktop computers.

And with the subsequent release of the spreadsheet program VisiCalc and the word processing program WordMaster, later WordStar, by 1980 computers had taken their place as a critical business tool.

As the computer industry grew, companies such as IBM, NCR and other hardware manufacturers began looking for applications for their products beyond the desktop. One of those applications was self-service.

But making those applications practical required the development of software to make their use worthwhile, giving birth to the kiosk software industry.

Alex in his younger days…

“Back then the biggest player was a company called Lexitech, founded by Alex Richardson in 1983,” said Ron Bowers, senior vice president of business development with kiosk and store merchandising provider Frank Mayer and Associates, Inc.

“Alex initiated the beginning stages of that through his work in the basement of a building at Yale University during his attendance there,” Bowers said. “He was behind the effort to help self-service technology grow from a curiosity to practical applications.”

At the time, IBM was holding large symposiums on college campuses, and they were looking for ways to provide information to attendees about seminars and conferences that were happening in various buildings, so the company approached Richardson to begin working the initial concepts for a solution. Richardson then brought in merchandiser Frank Mayer and Associates to help bring the concept to fruition.

“So the first program we did with them was this university solution,” Bowers said. “It resided on a huge IBM desktop computer that had very limited capabilities, but it was extremely cutting edge; way ahead of its time.”

That proto-kiosk was keyboard-controlled and offered little in the way of user experience, but it was able to access and provide information, giving a hint of what was possible with a self-service device. A subsequent effort involved creating a program for the city of New York for applicants to access information about job availability and submit an application.

Expanding from there

The kiosk industry, like many other technology-based industries that depend on interactions with customers, is like a two-sided coin.

On the one side is the technology component, where a piece of hardware performs a specific function. On the other is the customer behavior component, or knowing what the customer is seeking and the motivation behind their decisions. Companies don’t always bring the two sides together.

Lexitech recognized that dichotomy, Bowers said.

“Most of the other software companies that came out of that university connection were more interested in database management,” Bowers said. “Lexitech was the first to really get the idea that as an enterprise solution (the kiosk) was going to have to fulfill expectations and meet a need arising out of the consumer’s ability to shop in multiple layers and what motivates them to purchase.”

Lexitech brought a different direction to software development. It was no longer simply just the number crunching for which computers had traditionally been used; it was data crunching for an enterprise solution that involved both the retailer and the consumer, offering insights about products, features, benefits, specs and so forth to inform and educate the consumer.

“That is bringing the consumer and the product and the retailer together, and then being able to access that information through some type of a device,” Bowers said. “Back then the device was a freestanding kiosk. “

Lexitech eventually became Netkey and then sometime later NCR purchased them. Here is an Netkey_Solutions_Brochure.

Taking it to the masses

Much of that changed with the entry of St. Clair Videotex Design into the software arena. The company was founded in 1982 by Doug Peter, whose background was in advertising, brand marketing and public relations.

“St. Clair evolved and grew out of a design/graphics support for a larger marketing company,” said Chris Peter.

“(My father) Doug Peter was tired of doing endless ad buys (billboards, tv spots, etc.) and was looking for a way to measurably market and interact with consumers/public,” he said. “He wanted a system that was not only not intimidating but appealing to use, with real measurable results on the interaction that could be actioned on.”

St. Clair Videotex Design eventually evolved into St. Clair Interactive. At the time, kiosks were beginning to gain traction in the marketplace and seeing wider deployments, though the infrastructure, software and hardware solutions were painfully limited.

“Doug offered another perspective very similar to what Alex did at Lexitech,” Bowers said.

“He brought in the disciplines of advertising marketing and marketing strategy to the software,” he said. “I don’t use this term lightly, but I believe Alex was a genius for his time and place and what he brought into the mainstream because it did not exist before he did it. The same thing was true with Doug and his team.”

Peter brought in a different way of thinking, a different way of developing and a different way of presenting fact-based services to GUI and self-service merchandising, Bowers said, and that accomplished a number of goals. It helped build a brand for the retailer, and from a consumer standpoint, it began to offer them new and exciting ways to shop.

“It was growing by leaps and bounds because now it was bringing into the fold new strategies of inventory management, new strategies for introducing loyalty programs and managing and measuring sales promotions,” Bowers said.

In addition to bringing that advertising sensibility into kiosk software, Peter accomplished something equally important, developing a solution that would help reshape the industry.

“What allowed us to flourish and grow was that we didn’t just provide one niche solution (which was the general approach then, build out your solution, then sell it),” Chris Peter said.

“After we’d done our seventh Gift Registry solution, we realized that we could ‘template’ solutions,” he said. “Even the niche players had extensive professional service and customization costs associated with deployments, so we built out the base solution for solutions like Gift Registry, Catalog Shopping and so forth as well as Operations and Content Management tools that could control all of the base templates. This allowed our sales approach to become ‘what would you like to do’ instead of ‘here’s what it can do’, and I believe this was very successful for St. Clair.”

The corporate shift

Lexitech and St. Clair interactive weren’t the only software companies in the early days of the kiosk industry, although they were certainly two of the most influential. KioWare, PROVISIO (Sitekiosk) and others were also early entrants into the world of kiosk software.

“There was another company called Rocky Mountain Multimedia run by Dave Heyliger and Degasoft/Kudos,” said Nigel Seed, who served as the CEO of NetShift Software. “So those were some of the key competitors in that era.”

RMM was the first and only software application (Kiosk in a Box) that shipped as bonus software with every Elotouch touchscreen monitor. RMM still sells and ships its Pro Version.

Several of the largest companies to start the industry were companies like ATCOM/Info which ruled with their internet access pyramid, North Communications, Marcole Gift Registry, King Product, NeoProducts and more. Here is a list of companies by Frost and Sullivan n late 90s. Old Companies PDF and worth noting that several are current members of the Kiosk Industry Assocation (Gibco, TouchSource, Elotouch, USA Tech, KIOSK Information Systems and DynaTouch.

And following in the footsteps of Apple’s iconic “1984” Super Bowl commercial, many of those companies were small, scrappy players on the forefront of technological development.

“Going down memory lane, a company that comes to my mind as one of the first and main players for kiosk software was KioskLogix and their Netstop software,” said Heinz Horstmann, CEO of PROVISIO, the company behind SiteKiosk.

“When others were still in the beginning stages of kiosk development they had developed a software product for pay-per-use and other kiosks and public Windows computers that was available as canned download software which was easy to install and configure,” Horstmann said. “Netstop was one of the first kiosk software products that was successful on a national and international level.”

But as often happens in any emerging industry, large corporate concerns began looking at what those small players were doing and made decisions that would ultimately end up killing off many of the early entrants.

“I think all of us thought our customers would want to license a robust piece of commercial software,” Seed said. “To my horror I found a lot of the companies I was dealing with trying to license my software took a look at what we did and decided they could do it themselves.”

In addition, in the late 1990s Lexitech secured a patent on aspects of its kiosk software and began aggressively seeking to assert its rights under the patent. Some companies ended up folding, while others agreed to pay Lexitech a licensing fee. [You can still buy software today which bears the Netkey patent].

“Because of that, there was this poisonous aspect to the early start of the business that really didn’t help anyone in the end,” Seed said.

So as the industry began to take shape, it went through its ups and downs and some of the smaller players couldn’t hang on through the droughts. Others depended on specific hardware, some wanted control of the content, and some solutions didn’t integrate with other store systems, and so forth.

“As it has always been, the kiosk market was very feast or famine,” said Chris Peter. “Attending Kiosk Com and other shows, it was always a surprise to see who was new this year, and who wasn’t here from the year before.”

And in the eyes of many experts, the golden years for kiosk software developers were over after pay-per-use kiosks and public PCs became obsolete in North America and Europe, Horstmann said.

Many of those early players are gone, although some, such as KioWare and PROVISO, still survive and even thrive. Lexitech, which Alex Richardson renamed Netkey in 2000, was acquired by NCR in 2009. St. Clair Interactive, which won “Best Kiosk Software” awards for several years throughout its existence, is still operating, although in a much smaller form.

The widespread adoption of smartphones and the prevalence of their accompanying apps has certainly changed the direction of the kiosk industry, although kiosks continue to have a key role in the marketplace.

“If you ride the train every day you’re going to you’re going to use your mobile application to purchase the ticket,” said Bryan Fairfield, CEO of kiosk and digital signage software provider Nanonation.

“If you only ride it once a month, you’re probably not going to download their app,” Fairfield said. “In those cases, you might use an interactive (kiosk).”

Today, software has changed from the custom monolith model of companies such as St. Clair and Lexitech to more vertically and niche-oriented software, with many applications now based in the cloud. Devices that once were problematic, such as cash recyclers and kiosk printers, are now addressable via the network. Connected devices.

With the emergence of Chrome OS, the large base of windows legacy devices running on the Intel platform are finding new life. And many of the kiosks being deployed today are tablet-based, making mobile device management increasingly important.

Subscription-based cloud services are becoming increasingly popular to get set up and running fast and to avoid high IT infrastructure costs for self-service and interactive digital signage deployments.

And now we audibly and verbally talk to a cloud-based AI to hear the latest weather and find out “where’s my stuff” orders. Amazon Alexa and Google Home are becoming the interface.

“The focus continues to be on the cloud and how well kiosk software developers will be able to remotely deliver a tailored user experience for different industries,” Horstmann said. “Kiosk software solutions have to provide more than just security features and peripheral device support but also advanced remote management, monitoring and cloud-based content management solutions for a growing number of devices like tablets and interactive displays. “

Customers also have higher expectations for kiosk software in terms of scalability and ease-of-use, Horstmann said. Many companies are not willing to go through a lengthy setup and configuration process.

And today rather than having to write to some closed-door standards from the IBMs and NCRs of the world via NRF committees, we utilize the cloud with Html5 and JSON tying devices together on the Internet. The old giants just try to keep up. POS and self-order application development cycles are measured in days and months, not years anymore.

Hardware is no longer restricted to the stock Dell corporate PC with a 4:3 touchscreen. Kiosks now offer widescreen displays, tablets, content management, remote management and power over ethernet (POE) and the cloud. Forget big computers and requirements for USB always. Even Windows is becoming less important. All types of traffic analysis methods, authentication and beacons for realt time location. And then there is speech.

Jim Kruper of KioWare notes, “As far as software direction goes we see it heading in the direction of IOT which is really saying that kiosks will be connecting to a much more broader universe of devices. In addition, we see security features using biometrics finally becoming more mainstream as well as video technology that uses emotion detection and AI to drive user interaction.”

“Technology is changing every quarter,” Bowers said.

“New capabilities are becoming available and integrating with devices such as touch screens kiosks,” he said. “The important factor is it’s no longer the devices; it’s no longer kiosks or touch screens or digital signs. It’s the experience that comes out of the utilization of hardware; this retail marketing strategy which is much more effective much more insightful and much easier to respond to the changing interests and habits of today’s connected consumer.”

It’s coming.

Follow Up

- DigitalBusiness.US – for kiosk consulting and more contact the DB 🙂

- Kiosk History – going back pretty far is annotated history of kiosk industry we have been keeping for many years.

COMMENTS

Hi Craig – thanks for the trip down memory lane! The industry certainly has morphed and expanded over the years, it’s fascinating to see who is still viable as a provider, and who has fallen by the wayside.

In some ways, what we used to think of as “kiosk software” providing services to the public became “apps” on a smart phone giving access to an individual. Same workflow, just very different form factors. Yet, there are certain use cases where public access kiosk remains the best option for delivering information or automated service to the widest possible audience.

Hope things are well, keep up the good work! – Bob Ventresca (OG kiosk software dinosaur)

In our companion piece Richard Slawsky takes a look at one of the very first examples of technology developed.

[nextpage title=”All About PLATO”]

The birth of an industry

Insider Note: The beginnings of the kiosk industry periodically come up for debate. The writers of the world seems to all have the same preoccupation with “who’s first”. This is the argument for Plato, which was a school project basically and never “rolled out” to the public. Back then technology often started in the universities but the bigger question was how much of that actually was commercialized. In the kiosk world with kiosk people you are talking Florsheim or really Minitel and the French. We’ve always shortchanged the French (except their cooking…).

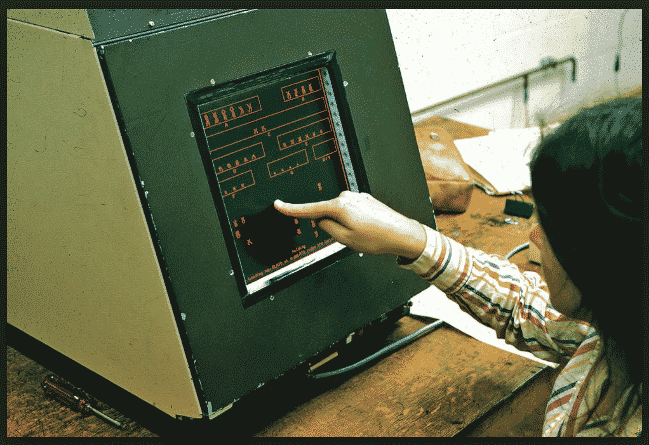

Although touchscreen kiosks are nearly ubiquitous today, it wasn’t that long ago that the technology was virtually unheard of. And while it may be difficult to pin the title of “Father of the Interactive Kiosk” on any one person, there is someone who can lay legitimate claim to the title.

In 1973, before he was a doctor, entrepreneur and pioneer in the field of workplace drug testing, Murray Lappe was a pre-med student at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign. Science fiction fans will recognize UIUC as the birthplace of HAL, the emotionally disturbed computer from 2001: A Space Odyssey. In the 1970s, Illinois was a hotbed of computing, with companies including Netscape and game maker subLOGIC having their roots in the university.

As a junior high and high school student in the Evanston School District in the suburbs of Chicago in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Lappe had taken classes in Fortran, writing programs using the punch cards that were the building blocks of coding in those days. So as a college student, it was an easy transition to the Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations, or PLATO, computer-assisted instruction system. PLATO operated on the university’s ILLIAC I computer, providing computer-based learning via thousands of graphics terminals around the campus and around the world.

“My freshman year probably more than half of my classes were on PLATO,” Lappe said during a conversation in early February.

“Chemistry, biology and physics were all PLATO learning classes,” he said. “We would go in to a classroom of terminals and pick up on our assignments wherever we left off. There might be a teaching assistant or someone, sitting in the front of the room if you had questions, but they were mostly self-guided.”

Although as a double major in math and life sciences Lappe was swamped in schoolwork, his advisor recommended he participate in some sort of extracurricular activity to enhance his chances of being accepted into medical school. His solution was to form the campus pre-med club, an organization for students like himself who also needed to participate in some form of activity. The pre-med club was one of about 3,000 or so organizations on the Illinois campus at the time.

The group limped along doing the occasional community service project, but in the summer before his senior year Lappe was invited by the Dean of Students to participate in a three-day retreat where attendees would brainstorm ways to improve extracurricular activities on campus.

During that retreat, Lappe found himself participating in a roundtable discussion on ways students could promote their organizations other than buying an ad in the school newspaper. Among the suggestions were a bulletin board where groups could post fliers promoting their group.

Lappe took the concept a step further, suggesting putting a list of those organizations into the PLATO system and developing a user interface to allow students to search out organizations based on their interests.

“We kicked the idea around, and it got some interest,” Lappe said. “After the session, the Dean suggested I apply for a grant to see if we could make it happen.”

Two weeks later, Lappe had a $2,500 check to develop the project. He spent the next few months sketching out ideas for an interface and developing the algorithm that would guide the search process. Once he’d hammered out the basic concept, he hired a computer science student, Mark Nudelman, to write the software.

“Murray started the design of the front page and sort of sketched out bits of the rest of the user interface,” Nudelman said during a mid-February interview. “I then fleshed it out and did all the coding.”

Over the course of the next six months they developed the PLATO Hotline, incorporating the ability to look up schedules for movies and other events around campus along with student organizations.

The final piece of the puzzle was the interface by which users would interact with the system. Donald Blitzer, then a professor of electrical engineering at the university, had developed a plasma touchscreen display in the early 1970s. Those displays were already being used on campus for the PLATO classes.

“I wanted to make it as simple as possible for people who had never used a computer before,” Lappe said. “I didn’t want it to look or feel like a computer.”

Lappe scrapped the idea of incorporating a keyboard, working with Nudelman to incorporate as much functionality as possible with the touchscreen alone. The end result was a simple interface with a “touch to begin” button launching the search process.

The PLATO Hotline debuted just a few weeks before Lappe’s graduation, set up in the middle of the student union building.

“It became a fascination,” Lappe said. “In the first 30 days 50,000 people had used it. There would be 50 people at any one time, 24 hours a day, waiting in line to try it out.”

Although Lappe desperately wanted to go to work for CDC, he realized this might be his only shot at attending medical school, and opted instead to attend Northwestern University and prepare for a career as a doctor.

Lappe left the University of Illinois just weeks after the launch of the PLATO Hotline, but the interactive kiosk remained a fixture of the student union for several years. Although the original kiosk featured a printer, that was soon dropped. A keyboard was added not long after launch, enabling users to enter their personal information for followup contact.

“That Macintosh was staring at me every day, and I was just waiting for the opportunity to find a computer problem that would let me quit medicine and go back to computing,” he said.

“And about eight years into my career the federal government passed a mandate that all transportation workers had to be tested for drugs,” he said. “And in that regulation there was a role for a physician to process the results from the laboratories that would do these drug tests. And it became immediately obvious to me that there was an opportunity to write software for a new industry.”

In 1998, Lappe founded eScreen, which provides drug screening management and automated hiring program solutions for companies around the country. In essence, his career has come full circle, putting him back in the center of the computer industry.

Still, he does wonder how things might have worked out if he had taken that offer from CDC. And he still feels a twinge of pride when encountering a touchscreen kiosk, which happens more and more every day.

“I’ve been telling my kids since they were little every time we go to an airport and walk up to one those board pass kiosks, that it all started with the PLATO Hotline,” Lappe said.

“I’m sure it was going to happen one way or another,” he said. “It wasn’t particularly novel. All the pieces were there; it was just a matter of putting them together.”

Kiosk History Extended

Elographics was founded in 1971. Now known as ELO.

The PLATO system was designed in 1977. Florsheim ran their store deployment in 1984 which was 600 stores and was first “endless aisle” kiosk.

Minitel rolled out in 1982 and experimentally in 1978. This was Videotext service over phone lines. It was an electronic phone book for the French public.

1982 was first opportunity for the US public to use a touchscreen at the 1982 World’s Fair (Elographics).

1983 Lexitech was founded by Alex Richardson

1985 touchscreens begin to proliferate thanks to Microtouch and Elographics (now Raychem).

In 1991, the first commercial kiosk with internet connection was displayed at Comdex. The application was for locating missing children.[1]The first true documentation of a kiosk was the 1995 report by Los Alamos National Laboratory which detailed what the interactive kiosk consisted of. This was first announced on comp.infosystems.kiosks by Arthur the original usenet moderator.

And for reference in 1955 Seeburg and Emerson release their “telejuke” which is sold to bars and includes a TV and a jukebox in a single enclosure. Link.